I

Daiei Film Studio

The precursor to Daiei Film Studio, Dai-Ichi Eiga, was formed in Kyoto in 1934 as a subsidiary of Shochiku Studio; in response to rival and competitor Nikkatsu Studio’s purchase of Tamagawa, a failed independent in Tokyo. Masaichi Nagata was appointed by Nikkatsu to run Tamagawa but within a month, after a dispute with management, he left and founded Dai-Ichi Eiga instead. Nagata, born 1906, had joined Nikkatsu, Japan’s oldest film studio, in 1924, working first as a guide, then a location manager, and subsequently rising through the ranks to become Head of Production.

When he resigned from Tamagawa he took with him many Nikkatsu stars. There were allegations he had been bribed by Shochiku to sabotage Tamagawa; it was said that the money used to set up Dai-Ichi Eiga came from an exclusive English school for children of the Kyoto elite run by Nagata’s wife. Be that as it may, in its short life, Dai-Ichi Eiga produced two indisputable masterpieces: Kenji Mizoguchi’s Osaka Elegy and its companion film, Sisters of the Gion (both 1936). When, that same year, the studio failed, Nagata became head of Shochiku-owned Kyoto film production facility Shinko Kinema.

In 1941 the Japanese government announced ten independent film companies were to be merged into two. These mergers were designed to give the government control over film-making; effectively, to turn film production houses into propaganda arms of the military. There was no possibility of resistance: raw film stock was classified as a war material and its availability to the studios would henceforth depend upon their making the kind of pictures the state wanted. Nagata was in a difficult position: under the two-company plan, Shinko Kinema studios would close, leaving him unemployed.

Nagata went public, claiming the plan, designed by Shiro Kido, head of Shochiku, was an attempt to consolidate Kido’s own power and that of his organisation. This endeared Nagata to others in the filmmaking community, many of them artists and writers, who also opposed the government plans, and they elected him to head a committee to canvas counter-proposals. As a Kyoto man, Nagata could take a more proactive stance than Tokyo people, who were in daily contact with the Office of Public Information. He suggested setting up a third company. The OPI realised that a third company, unencumbered by established management structures and old allegiances, could become its own public relations arm. Nagata’s plan was ratified.

Two Nikkatsu studios, Shinko and Daito, were combined to form Daiei (Dai-Nihon Eiga, or The Greater Japan Motion Picture Company) under Nagata’s management. His power increased when the board could not decide upon who to appoint as president and Nagata offered to take on those duties as well. He officially became President in 1947 and, apart from a brief period in 1948, when he was purged then rehabilitated by the Occupation authorities, remained in that position until 1971. Throughout this period he produced about a film a year, sometimes more; as well as a great deal of television.

After the war was over and Daiei’s propaganda activities, perforce, ceased, the studio faced a number of practical problems: no theatre chain and therefore no reliable distribution; a dearth of signed up star actors; lack of a back catalogue acceptable to the Occupation authorities, who had already restricted jidai-geki or period films because they were thought to encourage patriotic feelings of the kind which had fuelled the war. Kyoto, the old Imperial capital, was the centre of jidai-geki film making while Tokyo was where most gendai-geki, contemporary (post Meiji Restoration) films were made.

Nevertheless, production at Daiei continued at the frenetic rate attained during the war; one estimate, made by Teruyo Nogami, was that in the early 1950s they were turning out fifty films a year, that is, four a month or one every week. Nagata as a producer was commercially astute, with an eye to what would prove popular; but he had a genuine respect for artists and writers as well and would work to create the conditions in which they could realise their ambitions. He also loved baseball: the studio had its own baseball team, the Daiei Stars.

Without the luxury of big names on its payroll, Daiei started making exploitation movies instead, featuring themes like adultery and auto-eroticism. One Night’s Kiss (1946), by Yasuki Chiba, was the first to break the taboo against showing people kissing on screen. Daiei also produced, in 1949, the first Japanese science fiction film, The Invisible Man Appears. It was based upon the H G Wells novel and its special effects director, Eiji Tsuburaya, went on to work on the breakthrough sci-fi film, Godzilla (1954). In 1950 Nagata was invited (by the Italians) to send Akira Kurosawa’s film Rashomon to the Venice Film Festival where, in 1951, it won the Golden Lion.

In 1953 Daiei made Gate of Hell (Jigokumon), directed by Teinosuke Kinugasa; the first Japanese-made colour film released internationally. Filmed in Eastmancolor, it won the Grand Prix at Cannes in 1954 and took out Best Foreign Film at the Academy Awards. American film makers were transfixed by the way it cast a sheen of colour across subject matter that accorded with their own explorations of noir themes. Gate of Hell became a template for Daiei: a blend of the exoticism the West hungered after and the kind of picture which Japanese audiences would go to see.

Other innovations at Daiei in the 1950s included a Japanese Tarzan, Buruuba, in a picture shot in Hollywood; the making of erotic films for youths; and, mid-decade, some Taiyozoku (‘Sun Tribe’) pictures about disaffected youth, which included the smash hit The Punishment Room (1956) by Kon Ichikawa, made at Daiei, Tokyo. It featured a drug-assisted date rape and played morning to night with standing room only, primarily because of its appeal to students and especially to young women.

I

大映撮影所

大映撮影所の前身はである。第一映画社は松竹撮影所の子会社として1934年に京都に設立された。これは競合他社であった日活撮影所が、倒産した東京の独立系映画会社、日本映画多摩川撮影所を買収したことを受けてのことだった。日活から多摩川撮影所の経営を任されたのは永田雅一であったが、彼は経営陣と揉め、1ヶ月も経たないうちに退社した。永田が代わりに設立したのが第一映画社である。永田は1906年生まれで、1924年に日本最古の映画撮影所、日活に入社し、ガイドやロケ地監督などを経て制作部長に就任していた。

多摩川撮影所を辞める際に多くの日活に所属する人気スターを引き抜いたことから、松竹から賄賂をもらい、日活の事業を妨害したという疑惑を持つ者もいた。しかし一方、第一映画社の設立資金は永田の妻が経営する京都の上流階級の子弟のための高級英会話学校から出ていたと言われている。それはさておき、第一映画社はその短い一生の中で、映画史に残る2つの名作を生み出した。溝口健二の『浪華悲歌』とその関連作『祇園の姉妹』(共に1936年)である。同年、第一映画社が経営破綻したため、永田は松竹所有の京都の映画制作施設、新興キネマの所長に就任した。

1941年日本政府は既存の独立系映画会社10社を2社に合併すると発表した。合併は、映画制作を政府がコントロールし軍のプロパガンダ兵力に変えるためのものでもあった。この当時の社会情勢では映画会社に抵抗の余地はなかった。生フイルムの在庫は軍需品とされ、映画制作会社がそれらを使用するのは、国家が望むような種類の映画制作のみになった。新興キネマは閉鎖され、永田は失業し、独立することになった。

この頃、松竹のトップ、城戸四郎は、自身による組織作りを計画しており、永田はこれを城戸自身と城戸の組織の力を強化するための試みであるとし、公然と支持した。これが政府の計画に反対する芸術家や作家の多い映画業界人に好意的に受け入れられ、永田は立案対策委員会の議長に選任された。京都人である永田は、日頃中央の情報局と接していた東京人よりも積極的な姿勢を持っており、この委員会で第三の映画会社を設立することを提案した。情報局は、既存の経営構造や古い忠誠心にとらわれない第三の会社が、情報局独自の広報部門となり得ると考えて、永田の計画は認可された。

日活の2つの撮影所、新興キネマと大東興業が合併され、永田が経営する大映(大日本映画制作株式会社)が誕生したが、理事会は社長を任命することができず、永田がその職務を引き受けようと申し出たことで、永田の力は増していった。1947年に正式に社長に就任し、1948年進駐軍当局による短い粛清期間以降復職し、1971年までその地位にあった。この期間、彼は1年に1本、時にはそれ以上の本数の映画を制作し、また多くのテレビ番組も制作した。

戦後、軍部が推進するプロパガンダ映画を作る必要がなくなり、大映はいくつかの現実的な問題に直面した。系列の劇場がなく、確実な配給も約束されず、所属する人気出演者も不足していた。時代劇は戦争を煽った愛国心を助長すると考えられており、進駐軍当局の規制に会うようなバックカタログもなかった。時代劇映画の中心地は古都京都であり、東京では明治維新後の現代劇映画の多くが制作されていた。

しかし、戦時中から続く大映の狂乱的制作率は続き、野上照代の推定では1950年代初頭には年間50本、つまり、月に4本、週に1本のペースで制作されていたという。プロデューサーとしての永田は、何が人気になるかという商業的な直感を持っていたが、アーティストや作家を心から尊敬し、彼らの野望を実現するための条件を整えるために努力した。また、永田は野球が大好きで、撮影所にはダイエースターズという野球チームがあった。

大御所スターを雇う余裕もない大映は不倫や煽情性をテーマにした暴露映画を作りはじめた。千葉泰樹監督の『或る夜の接吻』(1946年)は、画面上でのキスシーンのタブーを破った最初の作品である。また、大映は1949年に日本初のSF映画『透明人間現わる』を制作した。H・G・ウェルズの小説を元にした作品で、特撮監督の円谷英二はその後、画期的SF映画『ゴジラ』(1954年)の制作に関わっていった。1950年、永田は(イタリアからの招待を受けて)、黒澤明監督の『羅生門』をヴェネチア国際映画祭へ提出し、1951年に金獅子賞を受賞した。

1953年には衣笠貞之助監督の『地獄門』が日本初のカラー映画として海外で公開された。イーストマンカラーで撮影され、1954年のカンヌ国際映画祭グランプリを受賞し、アカデミー賞外国語映画賞を受賞した。アメリカの映画制作者たちは、自分たちも探求しているノワール映画の主題に色の輝きを与える手法に魅了された。西洋が求めるエキゾチシズムと日本の観客の好みが融合した作品として『地獄門』は大映の雛型となった。

1950年代大映が制作した革新的作品の数々の中にはハリウッドで撮影された日本版ターザン、『ブルーバ』や若者向けのエロティック映画などが含まれ、1950年代半ばには、大映東京撮影所で制作された、市川崑監督の大ヒット作『罰室』(1956年)など、不遇の若者を描いた『太陽族』映画も制作された。薬物を使ったデートレイプなどを取り上げ、朝から晩まで立ち見席のみで上映され、主に学生、特に若い女性にアピールしていた。

II

Rashomon

Most of those who worked for Daiei in the immediate post-war years were young. Too young, perhaps, to have served in the war; but not so young that they hadn’t felt its effects. Teruyo Nogami was one. As a school girl of 17, at the Tokyo Club in 1941, she saw Mansaku Itami’s Akanishi Kakita (1936) and was so impressed by its satirical intelligence that she wrote a fan letter to the director. He replied immediately, sending her an inscribed copy of his Notes on Film and, although the two never met, they continued to correspond until Itami died from tuberculosis in 1946. She remained in touch with his widow, whom she did meet, in 1949; and it was contacts within the Itaman Club, formed after Itami’s untimely death, which led to her finding a job at Daiei.

Another member of the Itaman Club was Shinobu Hashimoto, a handsome young man who was prone to illness and endured many years of poor health. He was drafted during World War Two but found to be tubercular and sent to a sanatorium where he spent four years. Here a fellow patient one day lent him a film magazine; it had a scenario printed in the back and after he read it Hashimoto thought he could do as well or better than that writer had. He sent his first effort to Itami, who was both critical and encouraging. Hashimoto continued to write; through a complex series of exchanges, his adaptation of a Ryūnosuke Akutagawa story, ‘In the Grove’, found its way to director Akira Kurosawa, who added framing elements from another Akutagawa story, ‘Rashomon’, to form the basis of his 1950 film of the same name.

When Kurosawa, on a one year contract, came to Daiei to make Rashomon, Teruyo Nogami was assigned to his crew as script girl―responsible for continuity. She worked with Kurosawa for the rest of his career, becoming one of his closest colleagues, his production manager, and afterwards publishing an illuminating account of her experiences in the film industry. As for Shinobu Hashimoto, he went on to write more than eighty screenplays; Kurosawa directed eight of his scripts, including The Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood and The Hidden Fortress, which had a direct influence on George Lucas’s Star Wars movies. It’s said that Lucas derived the name Jedi, as in the Jedi Knights, from ‘jidai-geki’, the Japanese term for period films.

Teruyo Nogami remembered hanging out the window with other excited employees of Daiei the day Kurosawa and his entourage arrived. He liked to eat with cast and crew every night after filming; his favourite meal was sanzoku-yaki, beef sautéed in garlic. Afterwards they would smoke and drink and talk. These were social occasions but also opportunities to plan for the next day’s shoot. They continued to work as hard as they had during the war; post-war, they played hard as well. Many people used the drug philopon, a Japanese invention, a soluble amphetamine whose name means ‘love of work’. Nogami writes: the production crew would walk around with trays of capsules and syringes, inviting us to help ourselves or offering to administer the injection if we preferred.

The pressure of time and work encouraged innovation. Film stock was in short supply so few directors indulged in multiple takes of a scene. Sometimes music was written before the scene it belonged to was shot; these phantom compositions, called ‘ghosts’, were structured around the dramatic shape of the interaction in the screenplay. Often crews worked all night and then breakfasted in the canteen in the morning. Nogami in these years was also looking after Itami’s teenage son Yoshihiro (later film director, actor and writer Juzo Itami). She was so poor she sometimes had to pawn her clothes. Sometimes she didn’t have the money for the bus or train fare to work; but she never regretted her choice of vocation.

Kurosawa was himself an innovator. He refused to allow the crew to address him as Sensei, teacher, as was de rigueur then. He was happy smoking Japanese cigarettes, not the Lucky Strikes everyone else craved. Rashomon was filmed using a single camera and just three locations, one of which was the massive, ruined cedar gate which he had constructed, and which continued to stand for years afterwards at the Daiei Studios. When filming in the forest, he would use large mirrors to catch and then re-direct the sunlight; he also shot directly into the sun, unheard of until then. When he filmed the chase through the forest, rather than use tracks and a dolly, he had the actors run in a circle while using a 360 degree pan to capture their movement. He was so sure of his framing that he allowed Machiko Kyo, playing the Samurai’s wife, to wear running shoes below her kimono: he knew her feet would be out of shot.

Kurosawa preferred to record sound in situ, using a crystal motor to sync sound and image. He also post-recorded dialogue, where appropriate, outside. Mirrors would be set up in the back lot and, at night, when the trains from the nearby railway line stopped running, the actors would call to each other in the moonlight while the film played back in reflection around them. Another innovation was his insistence upon editing the work print. The custom in those days was for the editors to cut the negative according to their understanding of the script and only send through the relevant portions to be reviewed each night after filming had finished. This enraged Kurosawa; he wanted to see everything that had been shot during the day and edit from that. This method, like his habit of recording sound live, was adopted internationally.

Sometimes, after the day’s filming had wrapped, and everyone had eaten, actors and crew, including the director, would run up Wakakusa Mountain, overlooking the forest where they were filming and, when they reached the top, dance in the moonlight to the Tankobushi, the Coal Miner’s Song; which ended with everyone in a circle miming the action of a miner digging in the earth. Kurosawa said: I was still young and the cast members were even younger and bursting with energy. We carried out our work with enthusiasm. Rashomon took forty-two days to make and, despite a fire in the studio towards the end of the shoot, and then a second, smaller fire in a projection booth, was completed on time and made its way subsequently, to enduring acclaim, into the world.

II

羅生門

戦後初期の殆どの大映職員は若かった。従軍するのには若すぎたかもしれないが、戦争の影響を直接受けた世代であった。野上照代もその一人だった。17歳の未だ少女だった野上は、1941年に東京倶楽部で伊丹万作の『赤西蠣太』(1936年)を観て、その風刺的な知性に感銘を受け、監督にファンレターを書いたという。すぐに自筆入りの映画についての著書と共に返事を受け、二人は会うことはなかったが、1946年に伊丹が結核で亡くなるまで文通を続けた。その後未亡人と連絡を取り合い、1949年に初めて対面した。伊丹の無念の死後に結成された『イタマン会』内の人脈がきっかけで大映に就職した。

『イタマン会』には、病気がちで、長年不調に耐えてきた若い美男子、橋本忍がいた。彼は第二次世界大戦中に徴兵されたが、結核性であることが判明し、療養所で4年間を過ごした。ある日患者仲間が映画雑誌を貸してくれたのだが、裏にシナリオが印刷されていて、それを読んだ橋本は『この脚本家と同じかそれ以上のことができる』と思ったそうだ。橋本は伊丹に初のシナリオを送った。伊丹の批判と励ましを受けて橋本は執筆活動を続け、込み入った経緯を経て芥川龍之介の『藪の中』の翻案がやがて黒澤明監督の手に渡った。黒澤は芥川の『羅生門』のフレーミング要素を加えて、1950年の同名映画の基礎とした。

黒澤が羅生門を撮るために1年契約で大映入りした際に、野上はスクリプターとしてスタッフに配属された。それ以来、黒澤の生涯で最も親しい仲間の一人となり、制作責任者として働き、その後、映画業界での経験を綴った回想記を出版した。

橋本忍は80本以上の脚本を書き、そのうち『七人の侍』『血の玉座』『隠し砦の三悪人』など8本の脚本は黒澤が監督を勤めた。『隠し砦の三悪人』はジョージ・ルーカスの『スター・ウォーズ』に直接影響を与えたと言われる。ルーカスがジェダイ・ナイツのジェダイという名前は、日本語の『時代劇』と言う言葉からきていると言われている。

黒澤一行が大映を訪れた日、興奮のあまり、仕事仲間と窓から体を乗り出して迎えたのを野上照代は覚えている。黒澤は毎晩撮影後、キャストやスタッフと共に食事をすることを好み、お気に入りは牛肉とニンニクを炒めた山賊焼だったそうだ。食後、集まってタバコや酒を楽しむ時間は社交の場であると同時に、次の日の撮影の計画を立てる機会でもあった。戦時中から勤勉の倫理はすでに確立されており、戦後も同じように熱心に働き続け、同じように熱心に遊んだりもした。彼らの多くが日本製の可溶性メタンフェタミン、ヒロポン(philopon)と言う名の薬物を使用していた。ヒロポンは『仕事を好む』という意味だという。当時は制作スタッフがカプセルや注射器のトレイを持って歩き回り、希望すれば注射をしてくれたりしたと野上は書いている。

当時の映画撮影の現場では時間と仕事の圧力が革新を促していた。在庫フィルムが不足していたため、1シーンを何度も撮影する監督はほとんどいなかった。時にはシーン撮影前に音楽が作曲されることもあり、『ゴースト』と呼ばれるこれらの曲は、劇的効果を上げる場面を中心に構成されていた。徹夜で作業し、社内食堂で朝食をとることが多かった。その頃の野上は、伊丹の10代の息子、義弘(後、映画監督・俳優・作家の伊丹十三)の面倒も見ていた。当時の野上は非常に貧しく、服を質に入れることもあったそうだ。バスや電車での通勤費が足りないこともあったが、自ら天職を選んだことを後悔したことはなかったという。

黒澤もイノベーターだった。スタッフに『先生』呼ばわりされるのを嫌がり、国産タバコを好み、みんなが切望していたラッキーストライクは吸わなかった。『羅生門』はカメラ1台で撮影され、ロケ地はわずか3か所だった。そのうちの1か所は、彼が建てた廃墟となった巨大な杉の門で、その後何年も大映撮影所に立ち続けていた。

森の中での撮影では、大きな鏡で太陽光を捉えて、その方向を反射で転換させた。また、当時は誰も聞いたこともなかった太陽の直接撮影なども行った。森の中での追撃シーンの撮影の際、撮影用ドリーを使うのではなく、役者を円を描くように走らせて360度のパンを使って撮影したともいう。自らの撮影技法を自負していた黒澤が、侍の妻を演じる京マチ子に、着物の下にランニングシューズ着用を許可したのは、足元が写らないことを知っていたからだった。

黒澤は音と映像を同期させるために発動機を使い、音をロケ地の屋外で録音することを好んだ。また、台詞も必要だと思えば戸外で録音して用いた。夜、近くの線路を終電が通り過ぎてから、セットの後ろに幕を張って鏡を設置し、そこに映像を再生して、月明かりの中で役者同士が声を掛け合うシーンを撮影することもあった。他にも革新的と言えるのは黒澤の編集作業へのこだわりだった。それまで、監督は編集者が台本を解釈してネガをカット編集した部分だけをチェックするというやり方だったが、黒澤は日中に撮影されたネガの全てを見て編集したいと考えた。この手法は、黒澤の生録音と同様、その後国際的に採用されるものとなった。

撮影が終わり、全員が食事を済ませると、監督と俳優やスタッフが、撮影地の森を見下ろす若草山を駆け上り、頂上に着くと月明かりの中で踊った。黒澤は、『自分もまだ若く、キャストはもっと若く、はちきれるようなエネルギーで熱心に仕事に励んだ』と語っている。撮影終盤に撮影所の火災が発生し、プロジェクションブースでも小さな火事があったにもかかわらず、『羅生門』は予定通りに42日間の制作期間を経て完成し、世に送り出され、全世界の絶賛を浴びた。

III

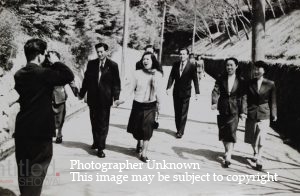

Photograph #238

Untitled.Showa Found Photograph #238 ファウンドフォト#238 Photographer Unknown 撮影者不明

The photograph shows a group of ten people. Nine of them are walking towards the camera, on a sunken path between a roughcast stone wall above which conifers grow, and another supporting a grassy slope where there are spindly, deciduous trees; the tenth has his back turned. It is a sunny afternoon, as can be seen by the way their shadows, and the shadows of the trees, are etched into the path upon which they are walking. From their clothes, you might assume it is cool not hot, early spring or late autumn; the spindly trees are bare of leaves. Maybe they are formally dressed because they are going to be photographed? Or are they on their way back, to the office or the studio, after the shoot?

This possibility is augmented by the fact that the one who has stopped and turned around is in the act of photographing the other nine. Which means that he is himself being photographed while taking a photograph. Those whom he is photographing are aware of what he is doing. They are pleased, amused, happy; perhaps someone has just cracked a joke. The photographer wears a dark suit. He is upright, poised, almost in a dancer’s pose as he holds the camera to his eye, while a finger on his right hand, we assume, is about to click the shutter; or has already clicked it.

Who are the other nine? The man nearest the photographer is tall and thin, wearing a rumpled suit and smiling in a crooked, self-effacing manner. He is accompanied by two women, whose hands he is holding. The woman on his right is obscured; the one on his left, wearing a white pullover and dark skirt, a scarf knotted loosely round her neck, and calling out to the photographer, is the centre of both photographers’ compositions. Perhaps she is the one cracking the joke; or making some derisive comment. If so, it is good-humoured, without malice or aggression; she is joshing.

The two women to the right of the picture, in step with one another, are smiling―at the photographer or at the joke, if there was a joke. They wear dark jackets over skirts that fall to mid-calf, good leather shoes. They too are holding hands. Behind are two more figures, one of whom is obscured by the woman with the scarf. The other is a suave, handsome man in a dark suit smiling in an enigmatic manner at the photographer. The other two people in the photo are so far away it is difficult to make out much about them, beyond noting that they are both women dressed, as most of the others are, in suit jackets and skirts and leather shoes.

Who is the photographer? Who took the photograph of him photographing? And who are these people? What are they doing? Two other photographs (#239; #237) give us some clues. In the first, thirteen people gather around the edge of a stone pool full of dark water. There are trees behind, and fragments of what look like fences. It seems we are in a park of some kind. The group is arranged around the corner of the pool, with those to the left with their feet on its very edge and those on the right standing on bare ground. The ambience is relaxed, informal, companionable. Most of them are smiling.

Untitled.Showa Found Photograph #239 ファウンドフォト#239 Photographer Unknown 撮影者不明

Amongst this group we can identify individuals from the previous shot. The woman with the scarf, for instance; the suave, handsome man, with his arm around a woman’s shoulder; the thin man, again with a woman on either side; the two suited women who were holding hands. Other identifications are less certain. The photographer in the dark suit, for instance, does not appear in this picture, suggesting perhaps that he is the one who took it. But if we go to the next photograph, a more formal shot, this time of sixteen people grouped together, before trees, on a forest path, there he is, in the front row, extreme right, with his glasses on and his camera held before him in his two hands.

Untitled.Showa Found Photograph #237 ファウンドフォト#237 Photographer Unknown 撮影者不明

Most of those who are recognisable in the two previous shots are in this one as well; though the woman is no longer wearing her scarf; and the thin man in the rumpled suite is absent: is he then a third photographer? If so, is there a doubling and re-doubling of perspectives in that first picture: a photographer taking a photograph of a photographer taking a photograph of another photographer? There are several women who do not seem to figure in either of the two preceding pictures. Only one of the women is smiling―she is one of those walking in step; the others look abstracted, even melancholy. The beautiful woman in the centre of the composition is looking out of the frame, as if she has just seen something disturbing there.

The men, too, are solemn; perhaps the photographer asked them to adopt a formal air. They are all wearing suits and ties, as the women wear jackets and skirts. All sixteen are bare-headed. The photographer has asked seven of the men to squat down on their haunches in the front, while eight women stand in a row behind them; behind them, incongruously, is the eighth man, handsome, with a large square head, who appears in the previous picture, the one by the pool, with an easy stance and his hands in his pockets; whereas here he looks like someone who does not quite belong.

When you look a bit closer at that line of women, the one fourth from the left seems ambiguous. S/he could be male or female; although s/he is wearing a suit jacket and a tie, the figure looks feminine and you wonder if s/he is, improbably, cross-dressing. Is she also one of those obscured in the first photo? In the centre of the row of squatting men is a small man with spectacles who also appears in the photo by the pool. He is older than the others; an executive; or a scholar. The rest of them are younger, in their twenties or early thirties.

They are clearly work colleagues who have, for whatever reason, decided to have photographs taken. The time is the early 1950s; chances are, they all worked at Daiei Film Studio; but in what capacity? Maybe they were in accounts; or transport; or in script development; maybe the women are from the typing pool and the men from the camera department. Or maybe they are a loose group of friends who work in a variety of different positions in the studio. Their casual familiarity with each other suggests they are colleagues who know each other well from working together and enjoy getting together after hours to have fun.

III

写真 #238

この写真には10人の人達が写っている。うち9人がカメラに向かって、上部に針葉樹が生い茂る荒い石垣と落葉樹を支える傾斜地の間にある長細い小道を歩いている。10人目は(カメラを構えて)後ろを向いている。彼らの影や樹々の影が、歩道に刻まれていることから、それは晴れた午後だと言うことがわかる。細長い木は葉を落としている。彼らの服装から見ると、春先や晩秋かもしれないが、写真撮影のために正装しているのか、あるいは撮影所や事務所での撮影の帰り道かもしれない。

止まって振り向いた男が他の9人を撮影しており、彼自身も写真を撮りながら撮影されている。撮影されている人は彼の行動に気づいていて、喜び、愉快で、嬉しそうだ。誰かが冗談を言ったのだろうか。カメラマンは濃い色のスーツを着ている。彼は直立し、姿勢を正し、ダンサーのようなポーズでカメラを構え、右手の指はシャッターを押す寸前のようだ。あるいはこの時にはもうシャッターを押していたのかもしれない。

他の9人は誰だろう?カメラマンに一番近い男は背が高く、痩身で、しわくちゃな背広を着て、ひがんだように控え目に微笑んでいる。彼には二人の女性が付き添い、手を繋いでいる。彼の右側の女性は見えないが、左側の白いセーターに黒っぽいスカートを履いてスカーフを緩く巻き、写真家に声をかけている女性は両写真家の構図の中心になっている。もしかしたら、彼女が冗談を言っているのかもしれない。もしそうであれば、彼女の冗談は悪意も攻撃性もない、朗らかでユーモラスなものだったのだろう。

写真の右側にいる女性二人は、互いに歩調を合わせ、写真家か多分その時に交わされた冗談に微笑んでいる。黒っぽいジャケットに七分丈のスカートを身につけ、上等な革靴を履いている。彼女達も手を繋いでいる。後ろにもう二人の姿があるが、そのうちの一人はスカーフを巻いた女性の後ろに隠れている。もう一人は黒っぽい背広に身を包んだ気品のある美男子で、写真家に向かって謎めいた笑みを浮かべている。後の二人は遠く離れているので、二人ともスーツジャケットにスカート、革靴を履いた女性であること以外はよく分からない。

撮影者は誰なのだろう。写真家を撮影している写真は誰が撮ったのだろうか。そして、この人たちは何者なのだろう。何をしているのか。他の2枚の写真 (#239; #237) が手がかりを与えてくれている。一枚目は、暗い水を湛えた石の溜池端に13人の人が集まっている。背後には樹々があり、柵のようなものの断片も見える。どこかの公園にいるようだ。彼らは溜池の角を中心に池を囲んで立ち、左側の者は淵に足を置き、右側の者は池のふちから離れて立っている。リラックスしたカジュアルな雰囲気で、仲間意識が伺える。ほとんどみんなが微笑んでいる。

このグループの中に、以前の写真にも写っている人達がいる。例えば、スカーフを巻いた女性や女性の肩に腕を回している気品ある美男子、またもや両側に女性を抱えている痩せ型の男性や、手を繋いでいたスーツを着た二人の女性など。他は確実ではない。例えば、黒っぽい背広を着た写真家は写っておらず、おそらくこの写真は彼が撮影したのではないかと思われる。16人が林道の樹々の前に集まっている次の写真では、彼は最前列の右端に眼鏡をかけ、両手にカメラを持ってそこにいる。

以前の2つの写真で見覚えのある人たちのほとんどが、この写真にも写っている。女性はもうスカーフを巻いておらず、しわくちゃな背広姿の痩せた男性はいない。もしかすると彼が3人目の撮影者なのだろうか。もしそうだとしたら、1枚目の写真には二重、三重の視点があるのだろうか。写真家が、別の写真家が、また更に別の写真家の写真を撮っている写真なのだろうか。前の2つの写真のどちらにも写っていない女性が何人かいる。一人の女性だけが微笑んでいる。構図の中央にいる美しい女性は、まるでそこに不穏な何かを見たかのように、横を見ている。

男性も厳粛な表情をしているが、写真家がフォーマルな雰囲気にしてくれと頼んだのかもしれない。みんな背広にネクタイを締め、女性はジャケットにスカートを着用している。16人全員、頭に何も付けていない。撮影者は男性7人に前にしゃがんでもらい、後ろに8人の女性が一列に並んでいる。その後ろに、8人目の、溜池の淵での写真では悠然とポケットに手を突っ込んでいた大きい四角い頭の美男子がいるが、以前の写真に比べ、ここでは居心地が悪そうだ。

女性の列を念入りに観ると、左から4人目が曖昧に見える。背広の上着を着てネクタイをしめているが女性的で、ひょっとして女性が男装しているのではないかとも思える。1枚目の写真に誰かの後ろに隠れていた一人だろうか。しゃがんでいる男性の列の中央に、溜池の淵での写真にも写っているメガネをかけた小柄な男性がいる。他の人より年上で、幹部か学者だろうか。あとは皆、20代か30代前半の若者のようだ。

彼らは明らかに、何らかの理由で写真を撮ってもらうことにした仕事仲間だ。時代は1950年代前半で、全員が大映撮影所で働いていた可能性が高いが、どのような立場で働いていたのだろう。もしかしたら、経理部や輸送部、脚本開発部などに所属していたのかもしれない。女性達はタイピスト班で男性達はカメラ班で働いていたのかもしれない。あるいは、撮影所内で様々な活動している仲間たちなのかもしれない。お互いのさりげない親近感から、お互いをよく知り、仕事の時間外にも集まり、楽しんでいる同僚であるらしいとうかがえる。

IV

Anonymity & Glamour

Some accounts say the girl who became actress Machiko Kyo was born Motoko Yano in Osaka in 1924. Others allege she was born in Mexico, where her father worked as an engineer. Her parents separated, in one version, while she was still young; in another, her father died when she was five and she was raised by her grandmother and her mother, a geisha, in the entertainment district of Osaka. An uncle took her to music hall shows and she began dancing―perhaps in the streets―when she was six or seven years old. By the time she was in her early teens, she’d changed her name to Machiko Kyo and joined a burlesque troupe. She made her film debut in Tengu Daoshi (The Tengu Did It), a hate-the-enemy film directed by Inoue Kintaro in 1944.

Five years she later was signed by Daiei, where Masaichi Nagata, with whom she may have become romantically involved, began promoting her as a sex symbol in the mould of Betty Grable or Hedy Lamar, hoping to arouse the interest of western audiences. Rashomon, in which Kyo starred, was a breakthrough for everyone involved. Even though Nagata, its producer, called it incomprehensible, it won an honorary Oscar for best foreign film, set box-office records for a subtitled picture and pioneered the so-called Rashomon effect, in which the same event is remembered in different ways. Pauline Kael called it the classic film statement of the relativism, the unknowability of truth.

Kyo also starred in Gate of Hell, the colour feature Nagata produced for Daiei in 1953. It is set in 1159, during the Heiji Rebellion, and tells the story of a samurai, Morito, who falls in love with a woman, Kesa, whom he has rescued. Kesa, played by Kyo, is a lady in waiting at the court and already married to another man, Wataru. Morito persuades her to conspire with him to kill her husband while he is sleeping; she gives him precise and detailed instructions as to how to do that. However, when Morito does commit the fatal act, he finds he has stabbed Kesa, not her husband. She has sacrificed herself to save Wataru and to preserve her own honour.

Gate of Hell had as profound an effect on American film-making as Rashomon, albeit for different reasons. Bosley Crowther, in the New York Times, wrote: The secret, perhaps, of its rare excitement is the subtlety with which it blends a subterranean flood of hot emotions with the most magnificent flow of surface serenity. The tensions and agonies of violent passions are made to seethe behind a splendid silken screen of stern formality, dignity, self-discipline and sublime aesthetic harmonies. The very essence of ancient Japanese culture is rendered a tangible stimulant in this film. In other words, American audiences were beguiled by the film’s use of colour as a splendid silken screen concealing, as it revealed, what was essentially a noir plot.

Kyo also starred in Mizoguchi’s 1955 film Princess Yang Kwei-Fei, playing a maid who becomes a princess; and a year later headlined the director’s last feature, Street of Shame, as a westernised woman prostitute who chews gum, overeats, and is a heavy smoker. Around the same time, Kyo went to Hollywood and made her sole American film, The Teahouse of the August Moon (1956), a satire upon the military occupation of Okinawa in which she appeared, opposite Glenn Ford, as a geisha named Lotus Blossom; her other co-star was Marlon Brando, in yellowface, cast, improbably, as Ford’s Okinawan interpreter. Kyo remained with Daiei until the studio filed for bankruptcy in 1971; and worked only intermittently, mostly in television, thereafter. She died, aged 95, in 2019.

This sketch of a biography suggests something of the ambiance of Daiei Studio in the 1950s, when those young people in the photograph were employed there. Working behind the camera, in whatever capacity, is not the same as being in front of it; but, as anyone who has worked upon a film shoot knows, the glamour of the cast belongs also to the crew; the same is true in the studio. At Daiei there were probably about a hundred and fifty staff in the various departments; they shared in the excitement of the artistic breakthroughs, of the breaking of sexual taboos, of the international successes which saw Japanese culture going out into the world. They lived a life full of possibilities, so apparent in the demeanour of those in this photograph.

Anonymity is the other side of the star system; the reverse of glamour if you like. Most people involved in the making of a film, which is inherently collaborative, only ever see their name in small print in the credits that roll at the end; and sometimes not even then. Contemporary practise is to list everyone who worked on a picture; even so, extras in crowd scenes or those who work in accounts, for example, do not usually make the credits. In the 1950s, only principals were acknowledged; everyone else had to be content that they and theirs knew what their contribution was. Not that there’s anything wrong with anonymity; after all, it is the fate of the majority of humankind.

Yet there is a poignant subtext to this photograph: perhaps some of those in it, whether they fulfilled their potential or not, were hoping for fame or fortune. Perhaps they wanted to achieve their ambitions in other terms, for instance by living a full and happy life. They might have done so; or they might have gone on to failures and disappointments, even to tragedy: the joy seen in this photograph is ephemeral and cannot be taken to mean anything other than what it was at the time. This is why anonymity in photographs is so suggestive: we want to know of the fate of these people and yet we doubt we ever can.

The German romantic poet Novalis said novels arise out of the shortcomings of history; meaning that whatever about the past we intuit but don’t actually know, we are tempted to invent. This photograph is so rich in detail it is easy to imagine a future for every person in it; and a past for each of them as well. This might or might not be a satisfying exercise; it would be better to know the actual life stories of those we see before us; but that is so unlikely as to be almost impossible. And yet: you never know. Something might still come up. Some wise old voice might speak and say: Oh yes, well, she . . . and as for him, he . . .

Posted July 2020

IV

無名と華麗

後に女優、京マチ子となった少女は、矢野元子として1924年に大阪で生まれたと言われている。また、父親がエンジニアとして働いていたメキシコで生まれたという説もある。幼い頃に両親が別居していたという説と、5歳の時に父親を亡くし、大阪の歓楽街で芸妓として働いていた母と祖母に育てられたと言う説もある。叔父に連れられて音楽ホールに行き、6、7歳の頃には、道端でかもしれないが、踊り始めていたという。10代前半頃には京マチ子と改名し、歌劇団に入団していた。1944年、井上金太郎監督の映画『天狗倒し』で映画界にデビューした。

5年後、大映と契約し、恋愛関係にあったと思われる永田雅一は、ベティ・グレイブルやヘディ・ラマーのようなセックス・シンボルとして、西洋の観客の興味を引くことを期待し、彼女を宣伝し始めた。京が主演した『羅生門』は、関係者全員にとって飛躍への突破口となった。プロデューサーの永田自身『訳がわからない』と言いながらも、アカデミー賞外国語映画賞を受賞し、字幕映画の興行成績も記録し、同じ出来事でも記憶が異なるという、いわゆる『羅生門効果』の先駆けとなった。ポーリーン・カエルは、相対主義、真実の不可知性の古典的映画による表現と呼んだ。

京は、1953年に永田が大映のために制作したカラー長編『地獄門』にも出演している。1159年、平治の乱を舞台に、武士の盛遠が宮廷の女官、袈裟に恋にする物語だ。京が演じる女官の袈裟は、すでに別の男性、渡と結婚していた。盛遠は、寝ている間に夫を殺すために共謀するよう袈裟を説得し、袈裟もその方法を細かく正確に指示する。しかし、盛遠がその致命的な行為に及んだとき、彼が刺殺したのは夫の渡ではなく、袈裟だったことに気づく。袈裟は渡を救うために、そして、自分の名誉を守るために自らを犠牲にしたのだった。

理由は異なるが、『地獄門』は『羅生門』と同様、アメリカの映画制作者達に大きな影響を与えた。ボスリー・クラウザーは、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙に、『おそらく、その稀有な興奮の秘密は、地中の熱い感情の洪水と、地表の静けさの最も壮大な流れを融合させる繊細さにあるのだろう。、厳かな形式、威厳、自己規律の崇高な美的調和の豪奢な絹紗の向こう側で、過激な情熱の緊張や苦悩が煮えくり返っていることだ。日本古来の文化の真髄を、具体的な刺激として与える作品だ。』と書いている。言い換えれば、アメリカの観客は、この映画の色遣いがノワール映画のプロットの本質を、見事な絹のような幕裏に秘めながらも明示していることに魅了されたのである。

京はまた、溝口監督の『楊貴妃』(1955年)でメイドがお姫様になる役で主演を務め、1年後に同監督の遺作『赤線地帯』ではガムを噛み、過食し、ヘビースモーカーである西洋化した娼婦を演じた。同時期にハリウッドに進出し、唯一のアメリカ映画『八月十五夜の茶屋』(1956年)に出演した。この作品は、沖縄の軍事占領を風刺したもので、グレン・フォードと共演し、ロータス・ブロッサムという芸者役を演じている。1971年に撮影所が倒産するまで大映に在籍し、その後はテレビを中心に断続的に仕事をしていた。2019年に95歳で他界した。

この大雑把な京の経歴は、写真に写っている若者たちが働いていた1950年代の大映撮影所の雰囲気を暗示している。どのようなポジションであろうが、カメラの裏で働く者は、表で働くものとは違う。しかし、映画撮影に携わったことのある人なら誰もが知るように、キャストの魅力はスタッフのものでもあり、撮影所自体も同じことが言える。大映には150人ほどのスタッフがいたと思われるが、彼らは芸術の躍進、性のタブーの解消、日本文化の世界進出、国際的な成功などの興奮を共有していた。彼らは可能性に満ちた人生を送り、この写真に写っている人たちの態度にもそれが表れている。

無名性は華麗なスターの反対側にあり、魅力の裏返しと言える。本来共同作業である映画の制作に携わるほとんどの人は、最後に流れるクレジットの中に自分の名前が小さく書かれているのを目にするだけで、時にはそれすらもないことがある。現代は慣習で、作品に携わった全員を一覧に表示することになっているが、群衆シーンのエキストラや会計の仕事をしている人などは、通常はクレジットにも含まれない。1950年代には、主要人物だけが表示され、それ以外の人は自分達の貢献が何であるかを知っているということで満足しなければならなかった。べつに無名性が悪いわけではない。結局のところ、それが人類の大多数の人間の運命なのだから。

しかし、この写真には痛切な意味合いが含まれている。おそらく、この写真に写っている人達の中には、自分の可能性を満たしているかどうかに関わらず、名声や富を望んでいた人もいたのではないでだろうか。または幸せな満ちたりた人生を送るという、別の形の望みがあったかもしれない。その通りになったかもしれないし、失敗や失望、さらには悲劇へと進んでいったかもしれない。だからこそ、写真の無名性が示唆に富むのである。私たちは彼らの運命を知りたいと思いながら、それができるかどうかは疑問に思っている。

ドイツのロマン主義の詩人ノヴァーリスは、小説は歴史の欠落から生まれると言っている。即ち、直感では知るが、実際にはわからない過去のことが何であれ、私たちはそれを「発明」したくなる。この写真はあまりにも詳細に描かれており、そこに写っているすべての人の未来と、それぞれの過去を容易に想像することができてしまう。これはこれで良いのか、悪いのかはべつとして、目に見えるこの者達の実際の人生の物語を知った方がより良いのだが、それは不可能に近い。しかし、それはわからない。まだ何かが起こりうる。賢明な歳を重ねた声が語ってくれるかもしれない。『そうそう、彼女は.、、、そして彼に関して、彼は、、、』

2020年7月投函

Note: photograph #238 is one of more than three hundred photos artist Mayu Kanamori found in a flea market in Daylesford, Victoria, about five years ago. The stall owner who sold them to her said they came from a deceased estate in Geelong but had no further information. They were all taken in Japan between about 1900 and 1960 and among them is photograph #213, which shows some of the same people in #238, standing in front of the Daiei Motion Picture Co. Ltd Kyoto Studio where, it seems, they worked.

注:写真#238は、アーティストの金森マユさんが5年ほど前にビクトリア州デイルズフォードのノミの市で見つけた300枚以上の写真のうちの1枚である。写真を売った店主によると、これらの写真はジーロングの故人が所有していたものだというが、それ以上の情報は得られなかった。これらは全て1900年から1960年頃に日本で撮影されたもので、その中に#213の写真がある。彼らが働いていたと思われる京都大映撮影所の前に立っている写真である。

Martin Edmond

マーティン・エドモンド

Martin Edmond / Artist supplied マーティン・エドモンド / アーティスト提供

Martin Edmond was born in Ohakune, New Zealand and lives in Sydney, Australia. He has written a number of books which might be described, loosely, as works of non-fiction. The most recent one is Isinglass, a ficcione about an asylum seeker, published by UWAP in 2019. Bus Stops on the Moon, an illustrated memoir of Red Mole theatre, will come out from Otago University Press in September, 2020.

Martin Edmond’s blog is here: https://mjedmo.wordpress.com/

マーティン・エドモンドはニュージーランドのオハクネに生まれ、オーストラリアのシドニーに住む。本人の言葉によると『ノンフィクションらしき』本を何冊も書いている著者。2019年UWAPから出版された『Isinglass』は亡命者を題材にしたフィクション作品。次作、レッドモール劇団の画像入り回顧録『Bus Stops on the Moon』は2020年9月にオタゴ大学出版から発売される予定。

ブログはこちらからhttps://mjedmo.wordpress.com/

Recent Comments